The website CBS Money Watch has up an interesting, but in my view ultimately wrong piece by Alain Sherter which suggests the U.S. economy is more likely than not to “slip into recession in 2016.”

The article first references the views of analysts from Citi Bank:

“In a December report, Citi Research analysts put the probability of the U.S. entering a new recession -- two consecutive quarters of shrinking economic growth -- at 65 percent. That prediction is partly rooted in history.”

Citi’s argument is based on the years that have passed since our last recession. In other words, a recession is due:

“Looking at previous recessions in the U.S., U.K., Germany and Japan between 1970 and 2014, the bank found that the odds of a downturn cross 50 percent roughly five years into a recovery. Notably, the U.S. is in year seven of its post-recession rebound.”

The timing argument by itself is not persuasive insofar as it offers no trigger for an economic downturn. In every recession, there is always some imbalance or excess which drives a withdrawal from the economy. Just because several years have passed does not mean our economy is out of whack or in need of a correction.

Mr. Sherter continues that “it's not only the past that augurs another economic slump … a number of headwinds threaten next year … the most powerful of these storms is the ongoing economic turbulence in China, Brazil, Turkey and other emerging markets.”

That is actually a novel suggestion, and Sherter concedes as much:

“For the U.S., a recession triggered by economic deterioration abroad would be a first.”

Mr. Sherter lays out what he believes has happened in the past to derail our economy:

“Typically, bouts of declining domestic growth are caused by a downdraft in domestic demand, often as a result of high interest rates that stifle borrowing and investment, decreasing wages, weak spending, eroding consumer confidence, rising prices and other factors that combine to short-circuit economic activity.”

Here Mr. Sherter largely misses the point. The U.S. economy normally goes into recession as a consequence of excess inventories. What he describes are aftereffects, failing to note what happened first to overheat the economy and thus why the various important negatives drove it down.

In short, this is what takes place when our economy recesses: There is full or nearly full employment. Consumers, who are workers, are buying the products and services that companies are making and selling. So more and more product is made. But companies eventually overshoot demand. And now some employers lack the sales to keep all their workers on the job. So they let the marginal people go. And that ultimately depresses demand even further. And at this point you have a vicious cycle: Where workers are being laid off until demand picks up; but demand falls more as workers are laid off.

For products like cars, bicycles, RVs, televisions, refrigerators, computers, smart phones, furniture, tools and so on, excess inventory used to be a much bigger problem in the past than it has been in recent decades.

There are a few reasons for the change.

One is that data moves faster. If cars are not selling, GM, Ford, Toyota and so on know that right away. There is no lag. They can reduce production immediately. They don’t want to get caught with a lot of inventory they cannot sell.

A second reason this is less of a problem for the U.S. economy is that a much smaller percentage of U.S. workers are employed manufacturing consumer durables like cars and tools. It’s not that we produce very little of these products here. We still do. It’s that those industries are much less labor intensive than they used to be. So the number of jobs lost when manufacturing slows down is much less than in the past.

The third reason is that for some industries — where the fabrication involves a lot of low-skilled labor, such as garments or shoes — nearly all of the manufacturing jobs have moved overseas. So if inventories of, say, Nike shoes build up too much, the first workers laid off will be in China and Vietnam, not Oregon or Maine.

Does that mean, then, that the inventory argument for recession is dated? No. It’s just that there is a special type of inventory which counts. That special type is real estate, especially housing, but also commercial real estate, including shopping malls and office buildings.

It is real estate which drives our economy on the margins to its heights; and when real estate inventories grow too fast for demand, it is real estate which pushes our economy into recession.

This has been true for all of the recessions in the United States since the early-1970s. Again, the recessions all along have been caused by excess inventories. But for the last 40-50 years, the key inventory has been real estate.

When there are too many houses, for example, that will not sell, builders lay off workers, home prices fall, workers buy less of everything else and the vicious spiral continues downward until the excess inventory is absorbed and demand picks up — often fed by government stimulus, like low interest rates or an infusion of cash into the economy.

Even though housing is far more important to the U.S. economy than commercial real estate, the 1990-91 recession began with an overbuilt office market, which itself was largely due to too much money from the Savings & Loans that had greatly relaxed their lending standards. That recession is often called the S&L recession, but it was triggered by an overbuilt office building market.

Unforntunately, the U.S. inventory equation is missing from Alain Sherter’s article. His focus remains on what is going on abroad. He argues, perhaps correctly, that foreigners have overdone their own inventories:

“After decades of investing in roads, factories, high-speed trains, housing and other hallmarks of a modern economy, these countries have too much industrial firepower and too little demand to sustain the hot-house growth required to justify all that spending.”

Again, the idea that this situation abroad will sink us is a novel argument. But I don’t buy it. That’s not to say that the American economy is not affected by what goes on internationally. Rather, that situation pales compared to what is happening here. Yes, U.S. manufacturers whose profits depend on exporting a lot of product overseas are harmed by the slowdown abroad. But marginal exports don’t play such a big role in our economy as real estate absolutely does.

The most important numbers to know at this point: U.S. home prices have been rising, significantly, and inventories of housing have fallen.

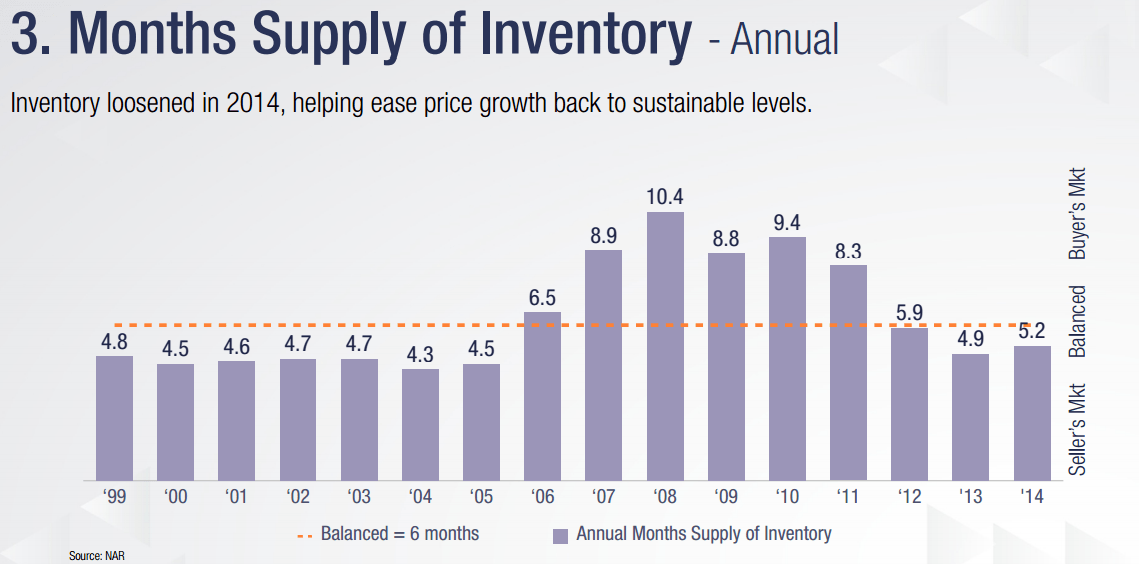

Home prices have risen 6.1% over the past year. Total housing inventory has fallen 3.3% to 2.0 million existing homes available for sale. Unsold inventory stands at a 5.1-month supply at the current sales pace.

According to the National Association of Realtors, real estate professionals consider a market where homes sell within six months of listing as “balanced” or “neutral,” meaning that enough homeowners are selling and customers buying that neither has an advantage.

Because homes are selling in less than six months on average, it is likey that demand is ahead of supply, and home builders are likely to increase production for awhile.

What would make me worry is if new home starts were going up much faster than the rate of economic growth in the rest of the economy and at the same time home prices were going up substantially faster than household incomes were growing. That is what we faced in the real estate bubble of 2002-08. It was driven by speculative investment, and it was entirely unsustainable.

The price of housing over the longer run should grow at about the same rate as household income grows. If new home starts are lagging, then prices might go up faster for awhile, until supply catches up. But when housing growth is strong and prices are going up too fast, it is just a matter of time before there is serious excess inventory.

Fortunately, that is not the case today. Housing starts have been modest. Inventory is normal. And price increases, while accelerating a bit faster than income, are not out of control and are likely to level off in 2016 and beyond as more product hits the market.

What would make me worry is if new home starts were going up much faster than the rate of economic growth in the rest of the economy and at the same time home prices were going up substantially faster than household incomes were growing. That is what we faced in the real estate bubble of 2002-08. It was driven by speculative investment, and it was entirely unsustainable.

The price of housing over the longer run should grow at about the same rate as household income grows. If new home starts are lagging, then prices might go up faster for awhile, until supply catches up. But when housing growth is strong and prices are going up too fast, it is just a matter of time before there is serious excess inventory.

Fortunately, that is not the case today. Housing starts have been modest. Inventory is normal. And price increases, while accelerating a bit faster than income, are not out of control and are likely to level off in 2016 and beyond as more product hits the market.

As such, we are not going to slip into a recession in 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment